Saturday, January 3rd

Precious

I woke up shortly before six. Beyond the curtains, the sky was overcast and I decided to go back to bed. When I woke up again shortly past eight, all the clouds had disappeared and the sun was out. This was more like it. I got up and soon was back on the road east.

I crossed Polaris Lake, drawn in optimistic blue in all maps but in reality a dried up yellow depression. The distance board announced 187 kilometres to Coolgardie and was followed by ‘Keep the scene clean.’ Good advice not only for motorists but also for directors and murderers.

Despite vegetation dominated by bushes, yet another sign announced the Great Western Woodlands. Soon indeed, as the land started to become hilly, the bushes were slowly replaced by trees. These were still spaced widely apart and left plenty of room for bushes and the charred remains of their predecessors.

Yellowdine, next services 156 kilometres, swooshed by. Marked in rather large letters on the map, it really only consisted of a petrol station on the right side of the road and an abandoned building on its left.

Soon enough the hills ended, the trees became smaller. The road entered Boorabbin National Park. It tried to pass by Boorabbin Memorial, but I decided to stop. At the parking lot a sign announced a seven hundred metre round trip to the memorial. I grabbed my new silly hat and went for a stroll.

A little over seven years ago, on December 30, 2007, a giant bush fire had started after a long drought. The fire raged north of the road for a while but eventually headed south. When it crossed the highway, it killed three truck drivers. They were remembered by a headstone at the end of the walk, engulfed in the eerie quiet of the bush.

Half way back was a shelter with displays recounting their lives but also telling the story of the once town of Boorabbin. It started out as a provisioning stop on the stage coach line east, grew once the railway came with its thirsty steam engines, and quietly disappeared when the trains replaced their thirst for water with one for diesel. Nothing was left of it now except for a labelled dot on the map.

Civilization reappeared in the form of dusty Coolgardie. It provided a number of rather impressive old white stone buildings, but they were far apart and looked slightly forlorn. In between was a number of smaller new buildings with shops, likewise forlorn. Perhaps this impression was only created by the ever present yellow dirt. I had hoped I for some coffee here, but decided to rather press on to Kalgoorlie.

A half hour drive through noticeably drier land, almost but not quite desert, and I entered the twin city of Kalgoorlie-Boulder. The flat, empty landscape offered plenty of space. The plots of the commercial operations along the road into town were accordingly large as were the first residential buildings, single-storey palaces, really. Further along, however, the buildings and surrounding plots returned to normal proportions.

The town centre of Kalgoorlie followed the customary pattern and ran along main street, called Hannah Street. It offered ample of parking so I did just that and started wandering its perhaps half a mile of sheet metal covered arcades.

It started in the south-west with the Town Hall, a turn of the last century yellow stone building complete with bell tower, now serving as the tourist information centre. The usual confusing assortment of shops and services followed. There were quite a few recruitment agencies focusing on mining jobs. Shopping was interrupted by a little square with a few benches under trees and currently sporting a decidedly fake Christmas tree. This looked a lovely spot for some coffee to battle the sleepiness that had befallen me on the last miles. Luckily there was a café just here for that very purpose.

One Flat White later I discovered the Court House and Post and Telegraph Office joined together by a large bell tower complete with golden roof. All three formed an impressive sandstone building. The post office part had been taken over by the courts, too, as the number of courts had grown and the telegraph had disappeared.

Another impressive old building housed the Miners Institute or possibly the Mechanical Institute, as there were signs for both. The intersection with Maritana Street featured hotels at three of its four corners.

At this point it may be prudent to suggest scepticism when an establishment in Australia refers to itself as a hotel. Quite often, these aren’t really hotels but pubs or restaurants. Particularly with older buildings it may be better to ask for a beer instead of a room.

The Australia, once more a pretty white sand stone building, however, promised ‘1st class accommodation.’ The Exchange Hotel across the street, a rather Germanic looking red brick building, was possibly just a large pub. The ensemble was completed by more white sand stone of the Palace Hotel. All of them featured a covered balcony running all along the second floor towards the street.

Further up Hannah Street became rather quiet at this noon hour, except for the local drunks as there were more pubs and clubs. Eventually, the street ended with a large metal girder mining tower announcing the Western Australian Museum.

I returned to the car and drove off towards Boulder. The road swerved around its centre, though, and instead a sign announcing the Super Pit Lookout caught my eye. The street it pointed to ran up a steep hill. It was thoroughly fenced in. A myriad of warnings signs made it clear that the land owners were not to be held responsible for any foolishness visitors would cook up.

Up top, there was a parking lot and a steep cliff. Beyond was Super Pit, an open pit mining operation of bedazzling proportions. The hunt was for nothing else but gold. The area was, in fact, called the Golden Mile. Discovered in the late nineteenth century, it soon had become home to some of the most profitable gold mines of all times. Subsequently Kalgoorlie and Boulder had sprung into existence and prosperity. But not enough, the twentieth century had brought allusions of grandeur. So far, there had been multiple smaller mines. These were combined into one giant company which then created Super Pit. It was to become a 3.8 kilometre long, 1.35 kilometre wide pit at its centre more than six hundred metres deep.

The mining process went something like this: first part of the wall was blown off with a decent amount of ANFO. Then giant diggers shovelled the resulting dirt into 225 tonne trucks which either carted it off or took it to the ore crusher for further treatment. From the lookout, the parade of the monstrous trucks hundreds of metres below looked not unlike a trail of ants.

Duly impressed, I returned to the car and the highway. Soon I was back in seemingly deserted bush. Yet dozens of power lines criss-crossed the country and gave away that the area was in fact littered with mines. Since most of them transported their produce by truck, road trains were allowed to be even longer: 53.5 metres. For more indications of mining, a tree by the road had been decorated with lots of hard hats that were now dangling off its branches.

It took only sixty kilometres to the next settlement, Kambalda. The map claimed that the town was sitting on the shores of Lake Lefroy, a rather large salt lake. But as I drove into town, the lake was nowhere to be seen. Instead, at its entrance there was a generous park with a football field and the tracks of a park railway. The town centre turned out to just be a tiny shopping area. The street kept going up and up a hill and eventually there indeed were glimpses of white beyond the trees. I circled the quiet residential parts of town and came to a sign pointing up a hill and promising Red Hill Lookout.

Red Hill turned out to be one of three of four hills the town was build on. One served as building ground for the aforementioned residential houses, one had the water reservoir up top. Red Hill only featured a radio tower and a picnic area. The lookout was duly pointed out to be three hundred metres that way (or six hundred round trip, as was also mentioned in a show of confidence in the public school system). Additionally, there was a seventeen hundred metre circuit around the hill.

I wandered off towards the lookout through red stones and tiny bushes. The lookout indeed provided grand views over the white plains of Lake Lefroy going almost all the way to the horizon. Two things made me decide against the circuit. One, a sudden paranoia about snakes hiding behind those stones and, two, an army of flies.

While by now I had gained a certain relaxedness with flies buzzing around my head, these critters preferred to crawl up my nose or into my ears which no amount of cool can make you ignore.

I rather went back to the car, shooed them away before opening the door, hurriedly jumped in and closed the door, and then patiently killed the four that still had made it inside.

After tangenting West Kambalda, similarly residential yet sitting much less pleasantly down in the flats, wilderness returned. It was interrupted only briefly for the brilliantly named Widgiemooltha, even though I was not really sure how to pronounce it. A long while later, wilderness finally ended after the road cut straight trough Lake Cowan, yet another huge salt lake.

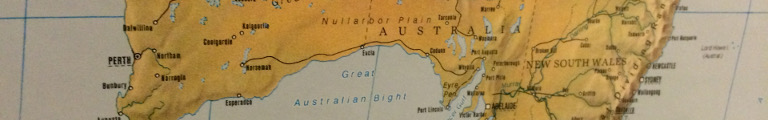

The slowly emerging civilization was part of Norseman. It started off with a large road intersection where Eyre Highway began, leading east through the Nullarbor Plain and eventually to Adelaide, 1986 kilometres away. A sign warned motorists that water supply was not to be relied on along this road and to the better stock up now while they still could.

To make the drive more interesting, at least if you were a golfer, there was Nullarbor Links, styling itself the world’s longest golf course. The first of its customary eighteen holes had been in Kalgoorlie, further holes were scattered along Eyre Highway.

Regrettably, I wasn’t planning on taking Eyre Highway, and not just because I really wasn’t a golfer. I considered ending the day here, as the next larger town down south was two hundred kilometres away by the ocean. I wasn’t sure if arriving past five would get me accommodation at the coast this time of year.

But Norseman was a rather sad place. There were two, possibly three overnight option none of which looked entirely right. The rest of the town had a rather run down, given up appeal. After driving around twice, I decided to take my chances and hurled myself south.

Wilderness was quick to be back and nothing much happened for the next hour. Then Salmon Gums appeared in the form of a petrol station and a school and a park and even a hotel (possibly even one with accommodation). Beyond, grass slowly returned and the land become noticeably more humid. Accordingly, the next village was called Grass Patch and provided a large grain storage facility. Now farming started for real. The landscape slowly turned into something that almost looked like home except for the trees which still looked all wrong.

About an hour ago, the sun had quietly disappeared behind a cloud layer. The temperature went away with it, down to only twenty degrees. But not to fret, near Gibson, perhaps twenty five kilometres to go, the sun equally quietly returned.

Not far, any more, to the coast and the city of Esperance. It turned out to be a bigger town as it featured a string of ugly enterprises along the approaching road. An information board had suggested that all hotels were placed along the ocean front, called Esplanade. Luckily, even the first hotel I checked still had rooms available so I ended the day.

Or not.

A ring road named the Great Ocean Drive lead through the beaches west of town that promised to have western exposure. And it has just become time to go chase after the sunset again. About half an hour’s drive away, I found Observation Point Beach, quite beautiful and perfectly situated. Sadly though, an impenetrable cloud layer lurked about a thumb’s width over the horizon, ruining everything. Or, well, almost everything. This still was a lovely beach, after all.

I returned to town by continuing the ring road. It ran by Pink Lake, so named because apparently it really was pink from some algae that lived in its salt water. In the current blue hour, however, it mostly looked, well, blue.